Far-right MEPs least disciplined in following party line

This article is part of an ongoing collaboration between Novaya Gazeta Europe and EUobserver to analyse European Parliament voting data.

In the upcoming European Parliament elections in June, far-right and eurosceptic politicians could significantly bolster their power, potentially securing a quarter of all seats.

While the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) is expected to maintain its status as the largest political group, the importance of each MEP’s vote is poised to escalate, particularly on divisive issues such as migration, agricultural policy, and green agenda.

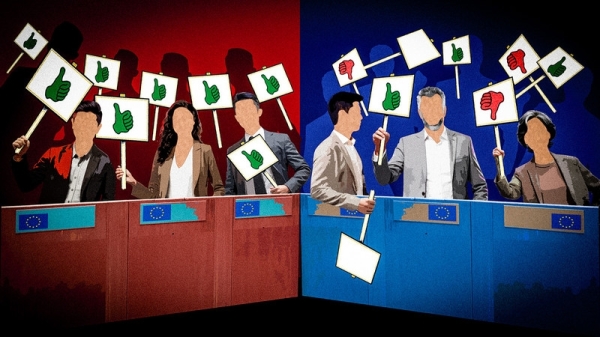

So this collaborative data investigation by Novaya Gazeta Europe and EUobserver aims to shed light on which lawmakers display the most obedient party discipline — and which MEPs most frequently deviate from their party leadership’s recommendations.

In the European Parliament, there are 705 MEPs, representing over two hundred national parties from 27 EU member states. To mitigate this fragmentation, each MEP, in addition to their national party affiliation, aligns with one of the European Political Groups (EPGs).

These political groups bring together national parties based on shared ideologies and perspectives on the future of the EU. For instance, the largest political group in the European Parliament, the centre-right EPP, comprises representatives from nearly 50 national parties across all EU countries. Additionally, six other political groups are spanning various points along the ideological spectrum.

Furthermore, a portion of MEPs operate independently, outside of any faction. As of 2024, there are 51 non-attached members.

European political groups play a crucial role in determining key positions within the parliament and receive more funding than independent MEPs.

However, for each MEP, their political group represents another ideological brand to which they must adhere, influencing how they vote in meetings. MEPs risk expulsion from both their national party and the pan-European group if they frequently flout the party line.

In a fractious parliamentry vote, the level of party discipline often decides the fate of legislation. And such votes may become more and more common in the next parliamentary term as far-right and eurosceptic forces strengthen their positions.

This analysis, which identifies the most undisciplined MEPs, and reveals that party discipline is the weakest among nationalists and far-right MEPs, is based on vote results during the last two legislative terms.

Brussels/Strasbourg vs US Congress

MEPs rarely deviate from party discipline, typically aligning their votes with the position of their political group and their national party.

On average, during votes in the last parliament, only four percent of MEPs voted against their pan-European faction.

The stringent discipline observed in the parliament stands in stark contrast to the behaviour of US congressmen, according to Anna Dekalchuk from the University of Glasgow.

This happens because US congressmen enjoy more independence compared to MEPs. Their relative independence stems largely from being directly elected by a majority in their constituencies, rather than solely through being on a party list.

On the contrary, European elections over the past two decades have been conducted solely under a proportional system, when EU citizens vote for party lists at the national level. Dekalchuk underlines that this system fosters a high dependency of MEPs on the leadership of national parties and European political groups, while weakening their reliance on individual voters.

First, MEPs risk their electoral prospects — something extremely important for any politician — if they go against their national party’s preferences, since such behaviour could result in them being simply omitted from the party’s lists by the national party’s leadership in the next electoral cycle.

Second, MEPs also depend on their political groups, especially if they strive for career advancement within the parliament governing structures, or if they want to push forward specific policies through writing reports on legislative proposals initiated by the European Commission, since both the posts’ and reports’ allocation is decided at the group level.

Alberto Alemanno, professor of EU law at HEC Paris, argues that the increased role of the EU parliament among other EU political institutions (which since 2009 has had the last word on the election of the commission president and their team), may also contribute to the high cohesion observed among MEPs from the groups supporting the EU Commission during votes in the last two parliaments.

Despite these factors, party discipline varies across European political groups.

Feisty Eurosceptics vs solid Europhiles

The conservative Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) group holds the record for the weakest party discipline in the last two terms of the European Parliament. Between 2014 and 2019, on average, almost a quarter of EFD MEPs voted against the majority position of their party group. In June 2019, the association dissolved itself as UK MEPs, who made up half of this group, left the European Parliament after Brexit.

In the current legislative term (2019-2024), the Identity and Democracy group (ID), has also proved to be the least cohesive. Every tenth ID MEP voted differently from what the group leadership expected of him or her. The European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR) also exhibits poor party discipline.

In contrast, party discipline is more stringent among mainstream European political parties. In the EPP and centre-left Socilialists & Democrats, on average, less than three percent of MEPs regularly vote differently from the majority. For The Greens/EFA, this indicator is even lower than one percent.

Two factors explain the reasons behind the lower voting cohesion among eurosceptics.

Firstly, the influence of these political groups is limited, as they secure fewer MEPs than the mainstream, pro-European political groups. Consequently, their leadership cannot advance an MEP’s career or policy preferences, as they seldom have the chance to promote their candidates to committee leadership positions or assign crucial reports to them, according to Dekalchuk. This dearth of leverage diminishes the likelihood of MEPs aligning every single vote with their group’s position.

Secondly, MEPs from ECR and ID are more oriented towards safeguarding perceived national interests, compared to their pro-European political parties, observes Alemanno. Simultaneously, the positions of national parties within those groups may significantly diverge on fundamental issues, such as migration. In such scenarios, an MEP will consistently align with the dictates of their national party leadership.

This assertion finds support in an evaluation of party discipline within national parties in the European Parliament. The top performers in terms of cohesion during votes are the conservatives and the far-right: Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party from Hungary, Marine Le Pen’s French Rassemblement National, and Matteo Salvini’s League in Italy.

Stubborn radicals vs timid Greens

When looking at MEPs individually, lawmakers from the ECR group show the lowest discipline. Seven ECR representatives rank among the top 10 MEPs least loyal to their political groups.

The most undisciplined MEP is Marcel de Graaff from the Netherlands. Before he left the ID in 2022, he voted against his group almost half of the time. De Graaff cited his pro-Russian views as the reason for leaving, advocating for the de-escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the lifting of all sanctions against Russia, and an end to arms deliveries and financial support for Ukraine.

De Graaff’s active pro-Kremlin stance has been previously highlighted. Out of the 22 parliament resolutions analysing Russian aggression, de Graaff voted against 16 and abstained from participating in the remaining meetings.

In second place for breaking the discipline is Charlie Weimers from Sweden, a member of the ECR. Despite holding the position of vice-chair in the ECR since 2022, Weimers has consistently voted against the majority of his group. He is also known for his extreme euroscepticism, having suggested the possibility of Sweden leaving the EU in November last year.

Conversely, the 10 most disciplined MEPs appear notably cohesive, with seven of them representing the Greens. Topping the list is Sara Matthieu from Belgium, who has never voted against the majority of the Greens since receiving her mandate in 2020. Overall, all MEPs in this top 10 have voted against the majority of their EPG less than 0.2 per cent of the time.

At the same time, one representative of the ECR, Karol Karski from the Polish Law and Justice party, was in third place among the most disciplined MEPs.

She is a member of the ECR bureau, which grants her direct influence over the group’s stance on key policies. Furthermore, Karski stands out from his ECR colleagues in terms of discipline, particularly due to his affiliation with an older generation characterized by a more right-conservative leaning rather than far-right.

In recent years, a generational divide has surfaced within the ECR. New MEPs who entered the parliament after the 2019 elections and nationalist parties, such as the Sweden Democrats, often exhibit voting patterns distinct from those of representatives from older parties like Law and Justice or the Brothers of Italy.

This split is evident in our data: the three ECR deputies among the top 10 least-disciplined are from the Sweden Democrats.

A centre-right/rightwing coalition 2024-2029?

The ID and ECR are poised to strengthen their positions in the upcoming EU elections in June. Forecasts suggest that their combined number of mandates could increase to 25 percent, with ID potentially gaining 40 new MEPs.

On one hand, the lower party discipline within the ID and ECR may limit their ability to assert their agenda in the European Parliament or block initiatives of mainstream parties. However, pro-european political groups will likely secure the loyalty of their MEPs on crucial votes, such as those pertaining to migration or climate.

On the other hand, the June elections could pave the way for a dominant centre-right/rightwing coalition in the European Parliament for the first time. This could materialise if the EPP actively involves the ECR in the allocation of key posts, for instance.

Following the elections, the ECR may see an influx of deputies from the Hungarian Fidesz party, known for its strong party discipline among national parties. In such a scenario, the Sweden Democrats may depart from the group, partly mitigating the generational conflict within the ECR and enhancing overall cohesion during votes.

However, the increased likelihood of ECR or ID deputies securing prominent positions in the new parliament or leading important reports on policy areas will provide the leaders of these groups with additional leverage over their members. Consequently, adept management of these opportunities to foster a pan-European career for their MEPs could lead to tighter party discipline within these factions.

Such developments could signify a closer alignment of the centre-right with conservatives and the far-right in the new European Parliament, significantly altering the EU’s political trajectory. This shift may particularly impact issues related to social policy, the green agenda, and attitudes towards Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Data collection and processing methods

Methodology: We gathered data from the parliament website on individual votes of MEPs, commonly referred to as "roll-call votes." During sessions, MEPs vote not only on documents as a whole but also on their individual components, such as paragraphs. To analyse voting results, we focused solely on final votes. In total, we analysed 4,001 final votes from the eighth and ninth term (spanning from mid-2014 to the end of 2023). We specifically selected final votes with at least 350 participating deputies to exclude technical votes requested by individual political groups.

To assess the level of party discipline, we compared how a specific MEP voted with the majority of MEPs in their political group or national party (abstentions were not included in these calculations). By determining the position of an political group or national party, we could then compare it with the vote of a particular MEP: for each final vote, we tallied the number of MEPs who voted against the majority of their group or party. We divided this by the total number of voting MEPs and multiplied by 100. Subsequently, we averaged these values for all votes over a given half-year.

To ensure accurate comparison of voting results between the eighth and ninth parliaments, we consolidated the data at the level of political group. While two European political groups changed their name and composition between the eighth and ninth parliaments (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe became Renew Europe and Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) changed its name to Identity and Democracies (ID)), they retained key ideological positions. The graphs reflect only the current names.